After the September 3, 2014 decision of the Court of Justice of the EU in Deckmyn v. Vandersteen, the notion of parody is a concept of EU law. Does it mean that the national cultures and laws of the EU Member States are no more competent to define the limits of humor? This would be rather unfortunate, if not funny! We can already anticipate the objections of the eurosceptics against this EU overhaul: British humor should remain what it is, insulated from any interferences by the European regulators… Should we fear the “europeanization of humor”?

The Deckmyn decision is not about the definition of humor, it is only about the definition of parody in the copyright context: indeed, Article 5(3)(k) of the 2001/29 Directive on copyright in the information society provides that Member States might exempt from copyright a “use” of a protected element “for the purpose of caricature, parody or pastiche“. Although the text refers also to caricature and pastiche, this exception is known as the parody exception.

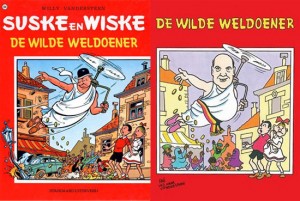

The facts of the case: at a New Year reception held in the city of Ghent in January 2011, Mr Deckmyn, a member of the Belgian Vlaams Belang political party, handed out small calendars. The cover page of those calendars reproduced the drawing depicted on this page, based on the cover of a Suske en Wiske (Bob et Bobette / Spike and Suzy) comic book entitled ‘The Compulsive Benefactor’.

The original drawing pictured one character wearing a white tunic and throwing coins to people trying to pick them up. In the Deckmyn version, the character was replaced by the Mayor of the City of Ghent and the people trying to grab the coins were replaced by people wearing veils and by people of color. The underlying message was clear enough and in line with the anti-immigrant view supported by this political party.

In the copyright infringement action brought by the author of the comic strip before the Brussels court of first instance, the defendant (supported by a foundation linked to the party) argued that the drawing at issue was a political cartoon falling under the parody exception provided in the EU Directive as transposed in Article 22(1)(6) of the Belgian copyright law. To support their claim that there was no parody, the plaintiffs put forward the parody criteria defined by the Belgian case law: to qualify as parody, a reuse of a protected work must fulfil a critical purpose; itself show some originality; display humorous traits; seek to ridicule the original work; and not borrow a greater number of formal elements from the original work than is strictly necessary (see for ex. D. Voorhoof, La liberté d’expression est-elle un argument légitime en faveur du non-respect du droit d’auteur ? La parodie en tant que métaphore, in A. Strowel and F. Tulkens (sous la dir.), Droit d’auteur et liberté d’expression, Larcier, 2006, p. 68). The presence of a discriminatory message was also an argument raised by the plaintiffs to oppose the parody argument. The Brussels Court of appeal referred several questions to the Court of justice of the EU.

The first one was whether the concept of “parody” was an autonomous concept of EU law. As already indicated, the CJEU responded positively to this question. This is in line with the recent CJEU decisions considering that several notions of copyright law (‘communication to the public” see here and here on ipdigit; “fair remuneration” for private copying, etc.) are to be defined at EU level so as to avoid an unharmonised interpretation of EU notions and the variations from one Member State to another (§ 16 of the decision). Harmonisation thus justifies that the CJEU be competent in areas pertaining to the freedom of expression. The recent CJEU case law is largely based on a balancing between several fundamental rights, including the freedom of expression (see for instance the March 27, 2014 UPC Telekabel decision of the CJEU, also discussed here on ipdigit). To realize that the CJEU, once focused on the economic freedoms of the EC Treaty, is now dealing extensively with other fundamental freedoms is a striking development which makes it more interesting than ever to compare its approach with the view of the European Court of Human Rights on similar issues. (I have recently written a piece about this in Rev. trim. dr. h., 100/2014, p. 889-911 entitled “Pondération entre liberté d’expression et droit d’auteur sur Internet: de la réserve des juges de Strasbourg à une concordance pratique par les juges de Luxembourg”).

The second question addressed to the CJEU was about the criteria for assessing when a parody (exempted from copyright claims) exists, and not just an adaptation (covered by copyright). The Court of justice underlined the role of the “usual meaning in everyday language” of the word “parody”. Relying on the opinion of the Advocate General, the Court listed two essential characterics of a parody: first it must evoke an existing work while being “noticeably different from it”; secondly, it must constitute an expression of humor or mockery (§20). The second condition requires from the national judges to decide whether the alleged parody contains (or not) “humor or mockery”. This aspect of the ruling might be critized (and be difficult to apply) as judges should not become the jury of what humor or mockery is (and are not best placed to do it). In any case, it shows that the definition of humor in the parody exception context remains within the ambit of the national judges and cultures, although it might be under the control of the CJEU at the end. The control by the CJEU should remain marginal as humor is contextually determined and varies according to nationality, age, gender, religion, ideology, social and cultural contexts, etc. (see D. Voorhoof and I. Høedt-Rasmussen, EU Court of Justice delivers preliminary ruling in Belgian Parody Case, 8 Sept. 2014, available here). In that sense, the possibility by the CJEU and, a fortiori, of the European Court of Human Rigths (ECHR), to control the definition of humor and parody will remain marginal. The scope for the review by the ECHR is in particular limited when a balance between several fundamental rights is at stake. The Deckmyn decision stresses that several fundamental rights do play a role as the objective of the 2001/29 Directive and in particular of its provision on parody is to harmonise copyright law in a way that takes into account “the fundamental principles of law and especially of property, including intellectual property, and freedom of expression and the public interest” (§25).

Here are a few additional comments and questions to consider in the discussion to start below:

First issue: the exception discussed covers not only parody, but also caricature and pastiche. Do you think it is worth to refer to those three types of “comments” (“genres” )? Are there arguments for having a law provision referring to parody solely or, on the contrary, to parody as well as caricature and pastiche?

Second issue: the Deckmyn decision makes it clear that the re-use of protected elements in the parody context is not only an exception to copyright, but that it is justified and protected by the freedom of expression (Art. 10 ECHR and Art. 11 EU Charter). The CJEU clearly states that “it is not disputed that parody is an appropriate way to express an opinion” (§ 25). Now the Deckmyn decision seems also to support the view that freedom of expression can justify a restrictive interpretation of what a parody is. Thus, more flexibility (than provided under the traditional Belgian interpretation: see on this the Limitations and Exceptions as Key Elements of the Legal Framework for Copyright in the EU, Opinion of the European Copyright Society on Case C-201-13 Deckmyn final) is needed to interpret the parody exception, on one side, but parody could be prohibited on the basis of freedom of expression, on the other side. Can you develop this idea? Does it mean that freedom of expression can thus favor, but also limit the speech for parody purpose? Is it a development to applaud or to fear?

Third issue: since Oct. 1, 2014, the UK Copyright Act provides for an exception for the purpose of parody. Do you think this exception as explained in official documents, for instance the Intellectual Property Office online guide (Exceptions to copyright: Guidance for creators and copyright owners, Oct. 2014), fits with the parody concept and criteria defined in Deckmyn?

Fourth issue: Do you think that the conditions for a parody to be exempted under trademark law (under the EU law) fit with the requirements recently outlined by the CJEU in Deckmyn?

Thanks in advance for your feedback on those issues, in particular on the fourth issue that you should discuss more extensively.