As already explained on this blog, crowdfunding has recently emerged as a novel way of financing new ventures. The basic idea behind crowdfunding is simple: instead of raising funds from a small group of sophisticated investors, entrepreneurs try to obtain them through the Internet from a large audience (the so-called “crowd”), where each individual provides a small amount.

For example, by early 2014, about 8,850 individuals pledged money online through the Belgium-based publishing house Sandawe; together they raised €850,000 to finance various projects of comic books. Sharing a similar business model, Akamusic allowed more than 80 artists to produce and distribute their album. While crowdfunding developed primarily in the arts and creativity-based industries, initiatives have been undertaken in other industries. For example, Angel.me, CroFun, Look&Fin, and MyMicroInvest are Belgian crowdfunding platforms that have experienced encouraging successes in raising funds for various entrepreneurial projects. Crowdfunding is naturally not confined within Belgian borders. Massolution reports that the market for crowdfunding has continuously grown worldwide since its infancy and should exceed $5 billion in 2013.

While crowdfunding is an umbrella term used to describe the request of funding from many individuals through an online platform, four types of crowdfunding models can be identified.

- First, crowdfunding can take the form of donations, where individuals give money to a given project and are not promised anything in return.

- Second, the reward-based model offers the contributors a non-financial benefit in return for their funding. In many cases, reward models offer the possibility to pre-order the product that the entrepreneur is making.

- Third, the lending-based model offers the possibility for entrepreneurs to act as borrowers, while contributors take the position of lenders.

- Finally, the profit-sharing model is a particular form of crowdfunding model in which contributors receive a share in the profits of the business or royalties of the artist. The latter model may also take the label of “equity crowdfunding”, meaning that it implies investments into securities: shares or bonds.

The startling rise of crowdfunding has raised awareness of and interest in its potential. It has also attracted the attention of scholars in finance, economics and management. Most of the studies on crowdfunding so far have an empirical nature (see, e.g., Agrawal et al., 2011, or Mollick, 2014); their goal is to better understand the motivations of funders and fundraisers, and to uncover the success factors of crowdfunding campaigns.

Although these empirical studies are very insightful, further research on crowdfunding needs to be informed by theoretical analyses, which have been scant up to now. Belleflamme, Lambert, and Schwienbacher (2014) make a first step in this direction. Our starting point is the contention that crowdfunding has implications that go beyond the financial sphere of the firm: it also affects the flow of information between entrepreneurs and contributors. In fact, raising money is not the only strong motivation for entrepreneurs. Other motivations for resorting to crowdfunding are seen as equally important; in particular, getting attention (reduced marketing costs) and obtaining feedback (market testing, market validation). Crowdfunding can be used as a promotion device, as a means to support mass customization or user-based innovation, or as a way for the producer to gain a better knowledge of the preferences of its consumers. Therefore, we argue that a deeper perspective on these other dimensions might help in our understanding of the dynamics of crowdfunding and enlighten the ongoing debate in many ways.

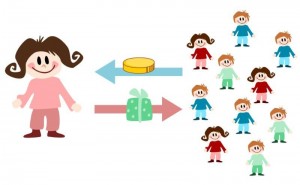

In the paper, we build a stylized model to understand what drives an entrepreneur to choose between the two main forms of crowdfunding, namely the reward-based and the profit-sharing models. To make the comparison as neat as possible, the two crowdfunding models only differ in two key aspects; all the other features of the modeling framework are common. In particular, it is assumed that the entrepreneur must raise a given amount of capital to launch her project; the cost of raising this capital is set, without loss of generality, to zero irrespective of the form of crowdfunding that is chosen. In other words, launching a reward-based or a profit-sharing crowdfunding campaign is supposed to be equally costly for the entrepreneur. It is also assumed that the entrepreneur faces the same crowd of investors/consumers in the two forms of crowdfunding; the crowd has no a priori preference for participating in one or the other type of campaign.

By “freezing” the cost and the participation dimensions, we clearly want to focus on another dimension of crowdfunding that we see as crucial, namely the relationship that crowdfunding allows the entrepreneur to establish with the crowd. The key argument developed in the paper is that this relationship differs across crowdfunding models. That is, when choosing one or the other form of crowdfunding, the entrepreneur also chooses what she can learn about the crowd and what she can extract from them through the pricing of her product.

Let us be more specific. The reward-based model of crowdfunding that we depict is based on pre-ordering: the contributors are consumers who have a strong taste for the announced product and who therefore decide to pre-order it, that is, to pay for it before it is actually produced. The entrepreneur can reward the contributors in various ways, as described above; what matters for the analysis is that these rewards (called “community benefits”) increase the contributors’ willingness to pay for the product. It is assumed that this increase in willingness to pay is proportional to the consumer’s taste for the product; that is, those consumers who like the product the most are also those who value the rewards the most. As a result, this form of crowdfunding allows the entrepreneur to segment her consumers into two groups: the early contributors who signal themselves as high-paying consumers (and whose willingness to pay is further enhanced by the value that they attach to the rewards), and the other, regular, consumers who wait for the product to be put on the market to consider buying it. The entrepreneur can thus price discriminate between these groups, which has the potential to raise her profits as she is assumed to be in a monopoly position for her product. However, the optimal price discrimination scheme may not be feasible if the initial capital requirement is too high. The obligation to finance the capital through pre-sales puts indeed a constraint on the price that can be charged to those consumers who choose to pre-order the product. One understands therefore that the profitability of this form of crowdfunding decreases with the size of the capital requirement.

The profit-sharing model differs with the reward-based model on two accounts. First, the nature of contributions and compensations is different: instead of pre-ordering the product, the crowd is invited to directly provide a fixed sum of money to the entrepreneur and is promised a share of the future profits in exchange. Second, contributors also enjoy community benefits but it is assumed here that these benefits are independent of the contributor’s taste for the product; this assumption makes sense as contributors are seen here as investors, who may well decide to finance the venture without purchasing the product eventually. The implications of these differences are the following. On the minus side, the entrepreneur is no longer able to segment the crowd and, especially, to single out the high-paying consumers. On the plus side, all individuals value community benefits in the same way, which makes it easier for the entrepreneur to capture this extra value; moreover, this ability to capture the value that contributors attach to community benefits is not impaired by the size of the capital requirement.

The comparison of the profits that the entrepreneur can achieve under the two forms of crowdfunding yields the main result of the analysis: the entrepreneur prefers the reward-based model when the capital requirement is relatively small and the profit-based model otherwise. The intuition behind this result has been outlined above: pre-ordering in the reward-based model allows the entrepreneur to practice price discrimination, which should give her a higher profit than in the profit-sharing model (in which she is bound to set a uniform price for her product). However, price discrimination is constrained, and thus less profitable, when the initial capital requirement grows larger than some threshold. Above this threshold, the profit-sharing model, which allows the entrepreneur to turn all individuals into investors, becomes the best option.