In 1572, Queen Elizabeth I of England commissioned Francis Drake to sail for America and encouraged him to plunder Spanish vessels on his way. Drake had thus all the attributes of a pirate, except that he was not working for his own account but for a government. This type of pirate was known as a “privateer”. Privateers presented the big advantage of allowing one nation to harry another one without officially attacking it. In other words, nations were avoiding the costs (and risks) of state-run warfare by outsourcing the “business” to profit-maximising entrepreneurs.

The “new privateers”

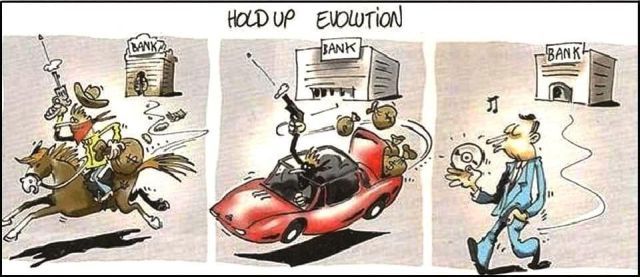

Although privateers disappeared with naval warfare in the 19th century (and an agreement by all major European powers to abolish it), they seem to have recently reincarnated into a new breed called “patent privateers”. Like their forefathers, patent privateers are armed by a powerful sponsor, with the aim of assaulting their sponsor’s rivals. In the 21st century version, sponsors—and their rivals—are established operating companies, mainly in the IT and consumer electronic sectors. The arsenal also differs from the 16th century version: instead of ships and guns, privateers receive patents and raids take the form of expensive and incessant patent infringement litigation.

Given that they do not manufacture any products (and thus, unlike their sponsors, are not restrained by any fear of “mutually assured destruction”), patent privateers could be mistaken with “Patent Trolls”, aka (in their new—and more politically-correct—denominations) “Patent Asserting Entities (PAEs)” or “Patent Licensing and Enforcement Companies (PLECs)”. Some commentators, however, see one subtle difference:

“unlike patent trolls, patent privateers share their revenues with others—the companies whose patents they purchased.”

Actually, it would be more correct to rewrite the end of the previous sentence as: “the companies who sold them their patents”. As David Balto (an Antitrust attorney and former policy director of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission) explained it recently in the Huffington Post:

“[O]perating companies transfer patents to trolls that have demonstrated a particular talent for “monetizing” patents. The transferring operating company typically maintains a perpetual royalty-free license for itself, and often extends a similar courtesy to business partners. The terms of the deal usually contain a payment schedule that enables the troll to earn more for meeting certain litigation milestones, thereby incentivizing the troll to leverage patents against the operating company’s competitors. The operating company may also maintain a right to a portion of the proceeds.”

Two recent and prominent examples of patent privateering agreements are between Microsoft, Nokia and MOSAID on the one hand, and Ericsson and Unwired Planet on the other hand. Both MOSAID and Unwired Planet (formerly known a Openwave Systems) are well known trolls, and both deals involve the transfer of more than 2,000 patents. As David Balto reports it:

“the contract between MOSAID and Microsoft/Nokia calls for MOSAID to reach “minimum royalty milestones” and Microsoft/Nokia’s right to collect a “shortfall payment. (…) The agreement [between Ericsson and Unwired Planet] is reported to contain a payment schedule that rewards Unwired Planet for success, and even contains a commitment by Ericsson to continue developing, obtaining, and feeding more patents to Unwired Planet over the years.”

Sponsors of privateers see nothing wrong in such deals: they are simply looking for the most efficient way to realize a legitimate return on their high and risky investments in intellectual property. Using privateers is efficient indeed as it allows operating companies to outsource litigation and to avoid a countersuit against their own operations; and if the competitors’ costs are raised in the process, even better!

Naturally, the targets of the privateers’ raids have a totally different opinion. Standing at the forefront of the fight against privateering is Google. Last month, Google wrote a letter (co-signed by BlackBerry, Earthlink, and Red Hat) to the FTC and US Department of Justice to ask them to take action not only against patent trolls but also against the companies who supply them with weapons. Google also claims that the US patent system over-rewards the work of coming up with an idea while taxing those who do the work of actually implementing it.

Economic analysis

Google’s claim epitomizes the difficulty that the patent system faces when dealing with sequential innovations. Sequential innovations are such that one innovation can only be achieved by using the results of another innovation; therefore, if the first innovation does not exist, nor does the second. If separate innovators are responsible for sequential innovations, then the question arises as to how to allocate IP rights among them. Ideally, one would like to give some rights to the initial innovator over the subsequent innovations as he/she contributed to make them possible; on the other hand, considering subsequent innovations as infringements to the initial one is likely to undermine later innovators’ incentives to invest. There is thus an inherent contradiction as the larger the rights granted to one innovator, the lower the incentives for the other one…

As modeled by Green and Scotchmer (1995), the problem becomes particularly acute when the first innovation is not valuable in itself; that is, it only becomes valuable through the extra value that the subsequent innovation creates. In that case, a ‘narrow’ patent (granting rights only over the first innovation) would not work as the first innovator would not find it profitable to invest in R&D; as a result, neither the first nor the second innovation would be produced. The first innovator must then be awarded a ‘broader’ patent, which gives him/her rights over the subsequent innovation. However, such a situation would put the second innovator at risk. This is the classic situation of holdup. The second innovator can rationally anticipate to be held up: once it has sunk the R&D cost of producing the second innovation, it will be in the first innovator’s best interest to appropriate the total value of the second innovation. Therefore, the second innovator will not be able to recoup its investment and will prefer not to invest. As a consequence, the second innovation will not be produced, and nor will be the first as the first innovator will not be able to appropriate enough value.

As Belleflamme and Peitz (2010, p. 528) further explain:

“In a more general setting, it can be argued that, because of the difficulties in dividing profit, patent lives will have to be longer than if the whole sequence of innovations occurs in a single firm. Then ex ante licensing (i.e., licensing before the second innovator sinks funds into R&D) is a way of mimicking the latter outcome. The other possibility is that licensing occurs ex post, i.e., after the second innovator has achieved the improvement or application of the first innovation. The difference, of course, is that the second innovator has sunk his costs at the time of the negotiation, which opens the door for opportunistic behaviour on the part of the first innovator (i.e., of holdup).”

Legal analysis

A sure thing is that the behaviour of privateers (and of their sponsors) is opportunistic. Yet, although such behaviour can be discussed on moral grounds, it is much harder to attack it on legal grounds. On a general level, at the core of intellectual property lies the right to (try to) exclude others. Both intellectual property and access to the courts are fundamental rights and parts and parcel of a market-orientated economy.

That being said, most rights are not absolute, and antitrust authorities in the EU and the US have undertaken recent (preliminary) actions with regard to the seeking of injunctions on the basis of a particular set of IPRs, so-called standard-essential patents (“SEPs”); see, e.g., the sending of a Statement of Objections by the European Commission to Samsung and Motorola as well as a draft consent decree between the US Federal Trade Commission and Motorola (Google).

Evidently, these actions do not target privateers. But, if they are seen through by the competition authorities and do not get overruled in court (e.g., the European Court of Justice has recently been called upon to rule on whether the seeking of injunctions on the basis of SEPs can actually be contrary to competition law), they would take one very important weapon out of the arsenal of privateers. They could no longer use injunctions against companies that are willing to take a licence under FRAND terms to twist the arms of the latter to achieve unjustified licensing terms.

Still, many issues concerning privateers remain unresolved: for instance,

- What if privateers still succeed in raising the cost of the sponsor’s rivals, e.g., by demanding very high royalties for SEPs or by seeking injunctions on the basis for non-SEPs? This question is linked to the more fundamental questions of how the increased activities of non-practicing entities affect innovation and competition and what, if anything, antitrust authorities could do (see, e.g., the workshop that the US Federal Trade Commission recently hosted on that topic).

- With regard to privateers, another question arises linked to the relationship between privateers and sponsors: could the agreement(s) between them run afoul of the antitrust laws?

IPdigIT and its readers would very much like to hear your views about these issues, and especially about the latter two questions.